Is Rio Ready for the Olympic Games?

The Olympics will likely go smoothly, but spending and construction for the games will burden the city for years to come, says journalist Juliana Barbassa.

July 28, 2016 12:57 pm (EST)

- Interview

- To help readers better understand the nuances of foreign policy, CFR staff writers and Consulting Editor Bernard Gwertzman conduct in-depth interviews with a wide range of international experts, as well as newsmakers.

The lead-up to the Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro has seen construction delays, contamination in water venues, and a spike in crime. (The Zika outbreak, at least, is waning.) Meanwhile, the state of Rio faces a massive budget deficit, which could exceed $5.6 billion this year. Brazilian journalist Juliana Barbassa says she expects the Olympics to go relatively smoothly, "but that misses the forest for the trees." Rio, like some other cities that have hosted the games, will likely be under a huge cloud of debt for years, she says.

A worker in downtown Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. (Photo: Kai Pfaffenbach/Reuters)

A worker in downtown Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. (Photo: Kai Pfaffenbach/Reuters)Do you think Rio will be ready for the Olympics?

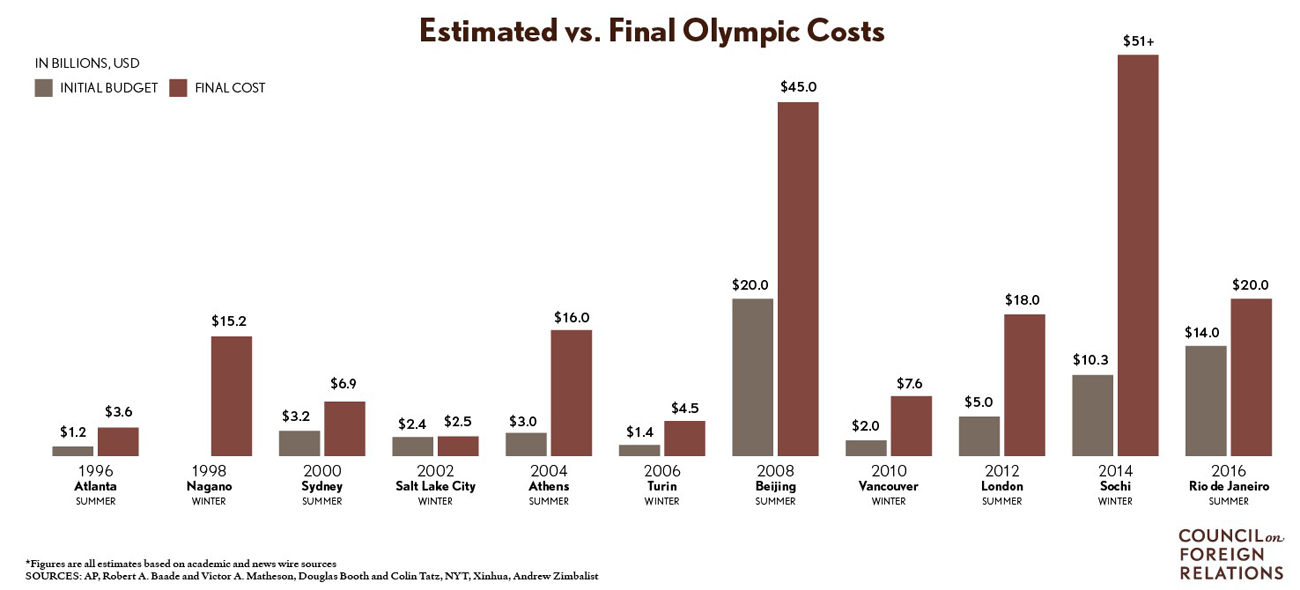

It will be like the World Cup. Rio is a beautiful city, and it’ll look fantastic on television. I think the venues will be ready and they won’t collapse, and the focus will be on the competitions themselves. People will say, "all the naysayers were wrong," but that misses the forest for the trees: Who pays the price for all this, and at what cost? Athens went into huge debt to host the games. In Rio, we’re already paying, and it’ll only get worse in the months and years to come.

More on:

This is not to mention that deep and radical transformations have reshaped the city over the last few years to accommodate this vision. It is more unequal than the city we had. Much of the infrastructural investment that did happen, such as in the tremendously expensive metro extension and the bus-rapid-transit lanes, went to the wealthy western neighborhoods. Projects that would have improved the lives of the working poor, such as a program that would have brought basic services to all of Rio’s favelas that the mayor called “the biggest social legacy of the Games,” were simply not implemented. That’s something we’re going to have to live with for a long time.

When Rio was chosen to host in 2009, Brazil’s economy was on the upswing. It contracted by nearly 4 percent in 2015. What happened?

Brazil’s economy was booming for reasons internal and external. China was growing and consuming so much of what Brazil sells: iron ore, soy, etc. China’s growth has slowed and commodity prices have gone down. Oil, which was discovered off Rio’s coast and was talked about as a solution to a lot of our problems and a source of funding for education and health care, is another commodity whose price went crashing down.

Not only did the money that had been coming in from commodities dry up, but the money that was expected to come in—the oil royalties—failed to materialize. That explains a lot of the deficit, at the national level and also in Rio.

"Petrobras is laying off hundreds of thousands of people and trying to get rid of assets. Brazil has suffered multiple blows in addition to the national recession."

One of the internal causes for Brazil’s boom was the growth of the middle class. Credit was made available to a huge swath of the Brazilian population, who bought cars and homes as well as washing machines, big TVs, and computers. That was a big engine for growth. But you only buy some of those things once, and once the economy started to contract, interest rates went up, and borrowing again became increasingly out of reach.

More on:

Meanwhile, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and suspended President Dilma Rousseff spent as if that boom were permanent. They increased government spending, from small things like increasing the number of ministries, which increased the number of people on the government payroll, to big subsidized loans to corporations.

Is the economy expected to improve in the near future?

Interim President Michel Temer is trying to cut back spending on a number of fronts without raising taxes and while dealing with a very fractious Congress. His goal is to renew trust in Brazil—for obvious reasons, Brazil is being seen by investors as a risky proposition politically and economically—but it’s difficult to pass anything at this moment. With Dilma [Rousseff] being impeached, with Congress divided and infighting, it’s difficult to even approve the necessary measures.

Brazil’s economy isn’t expected to grow until next year, or to register a primary surplus until 2019. People talk about Brazil’s "lost decade" [Editor’s note: This refers to the hyperinflation and low growth of the 1980s and early 1990s.], but between this year and last year it’s like we had another lost decade in just two years.

Why has the state of Rio been hit so hard?

Brazil increased its spending because it was betting on continued revenues into the future, and Rio did the same. Falling oil prices and the scandal involving state-oil company Petrobras, which is the biggest employer in Rio, are contributing to the budget deficit. Petrobras is laying off hundreds of thousands of people and trying to get rid of assets. Brazil has suffered multiple blows in addition to the national recession. Add to that the big spending attached to the Olympics.

The acting governor of Rio declared a state of calamity because the state is lacking resources to pay for its most basic services, like keeping hospitals open, cleaning schools, and paying police officers. But in that very same statement, he said that the state needs help meeting its international Olympic obligations. It shows how skewed the authorities’ priorities are.

Researchers and athletes have raised concerns over the contamination of Rio’s waterways, including Guanabara Bay, where some events will take place. During its Olympic bid Rio pledged (PDF) to clean them up. What happened?

Rio has had programs in place since the 1990s to clean up Guanabara Bay. A lot of money has been poured into clean-up efforts, but to virtually no effect. Why? Poor planning, mismanagement, and corruption—the same issues that dog a lot of major projects in Brazil.

Of the seven sewage-treatment plants built in the 1990s, for example, only three work, and at a fraction of capacity. They were constructed without systems to collect sewage from peoples’ houses and transport it to the plant. Authorities had poured a lot of money into these facilities, put all this equipment into them, and inaugurated them, but the hard and unpopular work, such as ripping up streets to install those connections, was never done. That approach to public works is something you see all over in Brazil, in Rio in particular.

"A lot of money has been poured into clean-up efforts, but to virtually no effect."

What Rio is getting now is a last-minute Band-Aid solution. They are using buoys and ropes stretched across the mouths of rivers—they call them ecobarriers—to block trash from entering the bay. That’s doing nothing for public health in communities upstream that don’t have adequate trash collection. All it does is keep the bulk of the trash from flowing into the bay during the Olympics.

Rio invested millions in community-policing programs aimed at reducing violence in the city’s favelas, yet homicides are up 15 percent from last year. What accounts for the spike in violence?

The economy is down, and there’s a lot disappointment in the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) program, which was very novel when it was implemented in 2008. It was a proposal to change the relationship between law enforcement and the populations they police, to do away with some of the antagonism that leads to such a high number of people killed by police and, increasingly, of police officers killed as well.

It was a good program in its limited application, but it was not a broad security program for the state, although it was talked about and used in that way. It was spread thin and expanded without enough officers to meet demand. Following the high-profile police killings of some favela residents, the population’s trust in this program was broken.

Interestingly, even though the violence has been going up in the past six months, the broader trend is positive. Rio and São Paulo are both safer than they were nine, ten years ago.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Online Store

Online Store